Date: April 28, 1993

Author: Valentina Krčmar, Toronto, Ontario

Addressed to: Letters to the Editor, The Globe and Mail

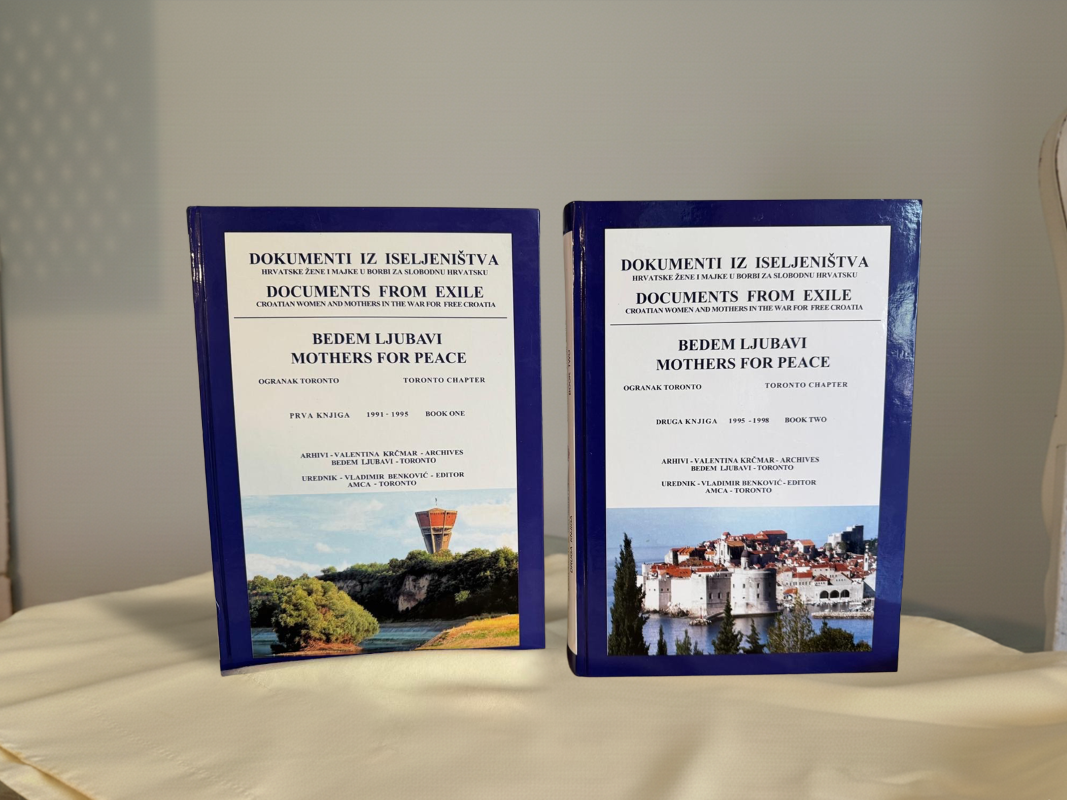

View the Original Letter: krcmar book 3_Part2_Part9.pdf

About This Letter

In this letter dated April 28, 1993, Valentina Krčmar delivers one of her most emotionally charged appeals to The Globe and Mail, written in response to an article titled “War Crime Executions Opposed – Canada Supports Sweeping Charges” (April 20, 1993). The article reported that Canadian diplomat Louise Fréchette, in a letter to the UN Security Council, opposed the use of the death penalty for individuals convicted of war crimes in the former Yugoslavia.

Krčmar’s response is visceral, raw, and deeply human — a cry of anguish from someone who has witnessed her homeland’s suffering while watching the world debate the moral rights of the perpetrators.

She begins by criticizing Canada’s position and expressing disbelief that representatives such as Fréchette could speak with authority about the fate of war criminals after years of silence and inaction.

“After two years of hands wringing and sighs about Croatia and Bosnia, how can Ms. Fréchette and Canada take a role in deciding what is going to happen with the war criminals from former Yugoslavia?”

Krčmar confronts the hypocrisy of those who defend the human rights of the accused while having turned away from the human rights of the victims. Her tone burns with grief and moral fury as she recounts, in stark detail, the tortures endured by civilians and hospital patients in Vukovar, Croatia:

“Victims had their throats or stomachs slit, were raped and maimed, quartered by electric saws, cut into pieces, skinned alive, burned at the stake, impaled by pitchforks — even young children — burned alive on barbecue pits.”

These harrowing descriptions are not sensationalism but testimony — a demand that readers confront what she calls “the horrors that sick demons dreamed of.” She reminds the world that most witnesses to these crimes did not survive, and those who did were forever scarred.

“The Serbs were smart, for not too many witnesses were allowed to live. Those that survived are mental cases. The horror was so great.”

Her words challenge the notion of procedural fairness for perpetrators of genocide when the victims were shown none:

“Human rights of the accused must be protected? What hypocrisy! Did anyone protect the human rights of our children and babies?”

Krčmar closes with a devastating appeal — that only the victims and their families hold the moral authority to determine the punishment for those responsible.

“Only mothers that have lost their babies to unimaginable horror, only wives who have seen their husbands killed in the most vicious way, or children whose fathers and mothers died in front of their own eyes begging for mercy — only these people can decide what can happen to the war criminals.”

This letter stands as one of Krčmar’s most searing indictments of moral complacency. It strips away diplomatic detachment and forces readers to confront the human cost of war crimes — reminding them that justice without empathy is no justice at all.