Date: November 14, 1994

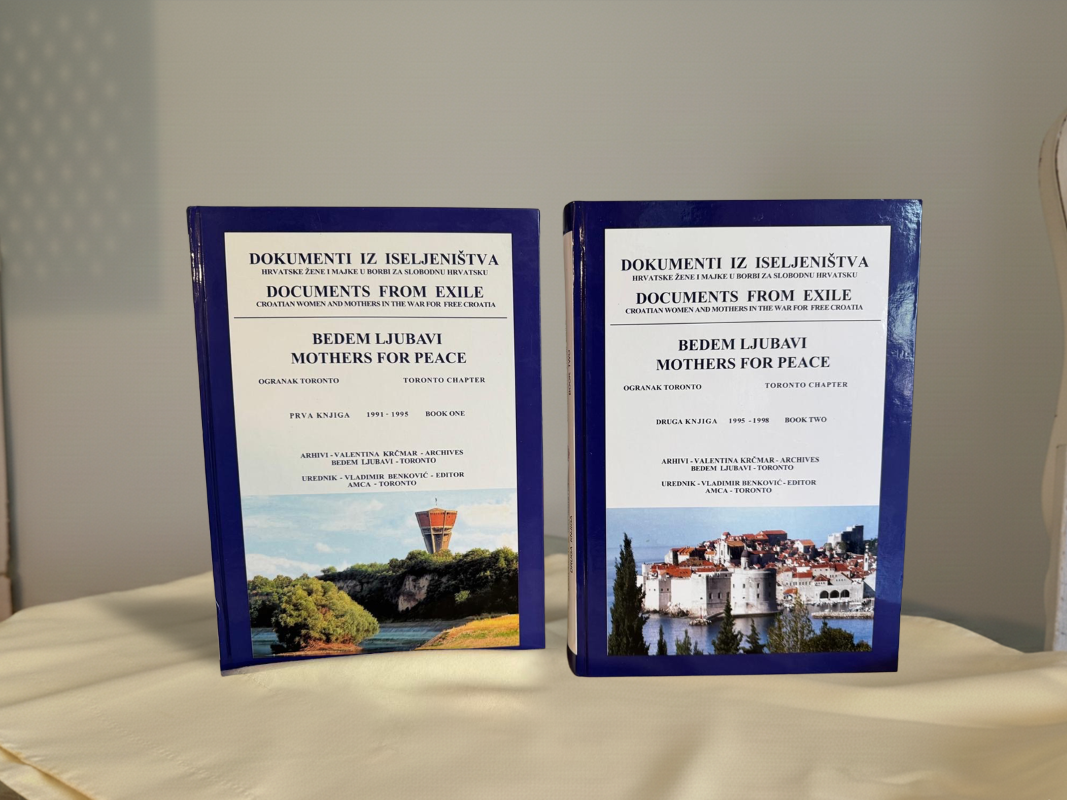

Author: Valentina Krčmar, Director, Mothers for Peace – Bedem Ljubavi (Toronto Chapter)

Addressed to: Professor Robert Prichard, President, University of Toronto

View the Original Letter: krcmar book 2_Part151_Part24-25.pdf

About This Letter

On November 14, 1994, Valentina Krčmar, writing on behalf of Mothers for Peace (Bedem Ljubavi), faxed a strongly worded protest to Professor Robert Prichard, President of the University of Toronto, condemning the university’s decision to allow Srdjan Trifković — political advisor to Radovan Karadžić, the Bosnian Serb leader later convicted of genocide — to speak at an event organized by the Serbian community in the Sanford Fleming Building.

Krčmar’s tone is urgent, emotional, and deeply moral. She begins by outlining the event details as announced on Serbian Radio, expressing disbelief that a Canadian university would host a figure associated with the architects of ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia:

“We are protesting that the premises of our university, the school where many of our children went and are still going, and which is being funded by us, the taxpayers, are being used for the propaganda lecture for the Serbian cause.”

She appeals to Prichard’s sense of ethics and historical awareness, contrasting the university’s academic prestige with the moral consequences of hosting a propagandist for genocide:

“We are appalled that in times like today, when the whole civilized world knows what has happened in Bosnia — that over 200,000 people died, that millions are being ethnically cleansed, many thousands of women and children raped, and concentration camps with thousands tortured to death — that you, as a scholar and the president of the University of Toronto, allow the adviser to the war criminal to speak from the pulpit of one of our finest universities.”

Krčmar acknowledges the principle of free speech but distinguishes it from deliberate misinformation and hate propaganda:

“The democracy is one thing, propaganda another. Although we all believe in freedom of speech, we hope that you also believe in the protection of innocent victims by not allowing such people to have their say.”

She implores the university to withdraw permission for the event, arguing that allowing Trifković to speak on campus legitimizes denial and desecrates the memory of the victims:

“We are asking you to withdraw the permission for Mr. Trifković and others to speak, because the University of Toronto should not be the place for influencing our young minds with lies, defamation, and slander.”

Her closing lines are poignant and resolute — a mother’s voice demanding dignity for the dead and accountability for the living:

“Our victims, even in their death, need protection by us. It cannot be allowed that anyone is permitted to slander those that died or are dying even as we write this letter to you.”

This letter captures Krčmar’s characteristic blend of moral conviction, emotional clarity, and civic engagement. It reflects her lifelong belief that freedom of speech must never be weaponized to justify atrocity, and that institutions of learning bear a special duty to uphold truth and human dignity.