Date: April 13, 1993

Author: Valentina Krčmar, Thornhill, Ontario

Addressed to: Letters to the Editor, The Toronto Star

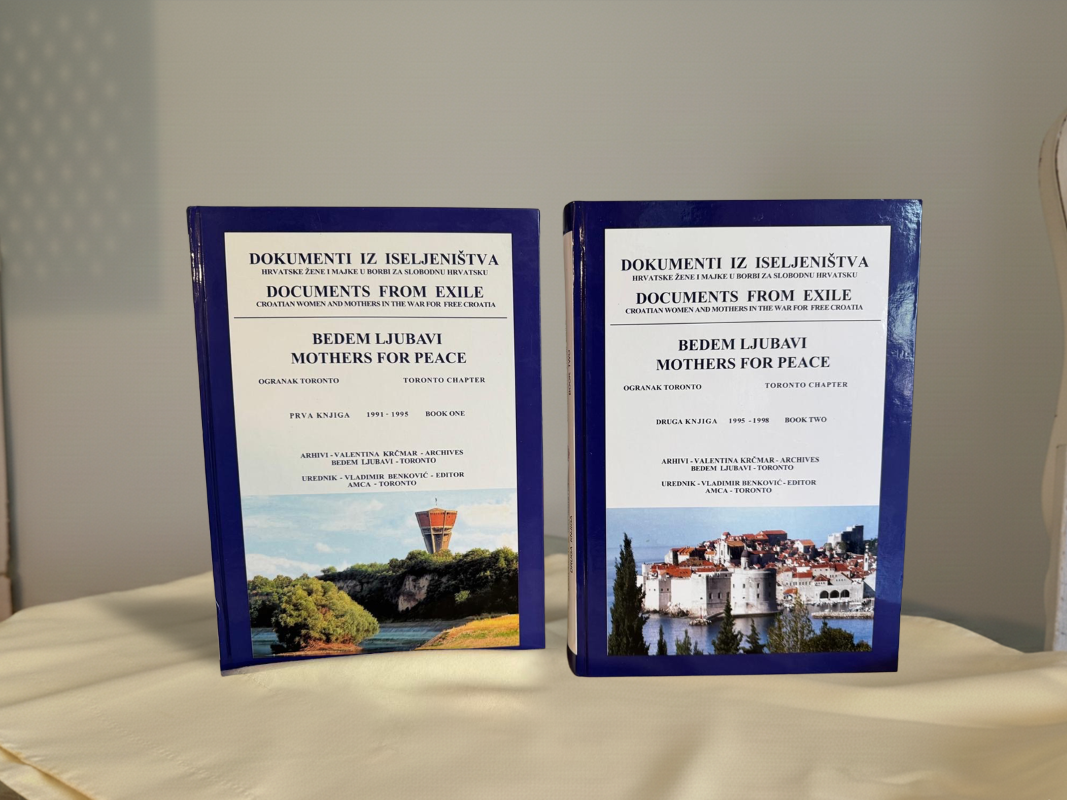

View the Original Letter: krcmar book 3_Part2_Part57.pdf

About This Letter

In this letter dated April 13, 1993, Valentina Krčmar writes to The Toronto Star in response to the article “Yeltsin Seeks Delay in U.N. Vote” (April 12, 1993). Her tone is laced with bitter irony, exposing what she perceives as Russia’s complicity in perpetuating the suffering of Croatians and Bosnians during the war.

She begins with biting sarcasm:

“The Serbian nation will probably erect a monument to the most important ally of the Serbs — Yeltsin. He has certainly proven that he is a true brother and friend to every red-blooded Serbian all over the world.”

Krčmar denounces the Russian president’s repeated efforts to delay or weaken sanctions against Serbia, accusing Moscow of shielding a brutal aggressor from accountability. Each diplomatic hesitation, she argues, translated directly into more death, rape, and displacement across Croatia and Bosnia.

“All these so-called actions against Serbia have resulted in further torture, deaths, rapes, ethnic cleansing and misery of the populations of two countries, Croatia and Bosnia.”

Her letter paints a grim picture of a world order complicit through inaction. Even the newly established “no-fly zone,” she notes, was a hollow gesture — planes “not shooting down the culprits,” merely “escorting them.” The hypocrisy of Western aid to Russia compounds her frustration: while nations pour billions into Russia’s recovery, she asks, how much of that support ends up sustaining Serbia’s war effort?

“Do the Serbs have to worry about the sanctions? They certainly don’t. Their good friends, the Russians, will do whatever they can so that their friends do not suffer.”

Krčmar contrasts Russia’s protection of Serbia with Croatia’s burden of compassion — a nation under siege that still shelters over 700,000 Bosnian refugees. Her voice swells with quiet pride as she declares:

“I am Canadian Croatian, and with every day I am more proud of the country where I was born — Croatia. It made sure Bosnians have a place they could call home.”

In closing, she condemns the moral inversion of global politics — where aggressors enjoy allies and victims are left to fend for themselves. Her words cut to the heart of moral clarity amid diplomatic deceit:

“The Serbs are ‘lucky.’ They have their Russian brothers to protect them. We, Croatians and Bosnians, have only each other… And yet, I would never want to belong to the nation for which Mr. Yeltsin tried to delay the vote in the U.N.”

This letter captures Krčmar’s deep indignation toward the global powers whose political maneuvering prolonged human suffering. With pointed irony and fierce loyalty, she exposes the moral blindness that allowed injustice to thrive behind the veil of diplomacy.