Date: August 14, 1995

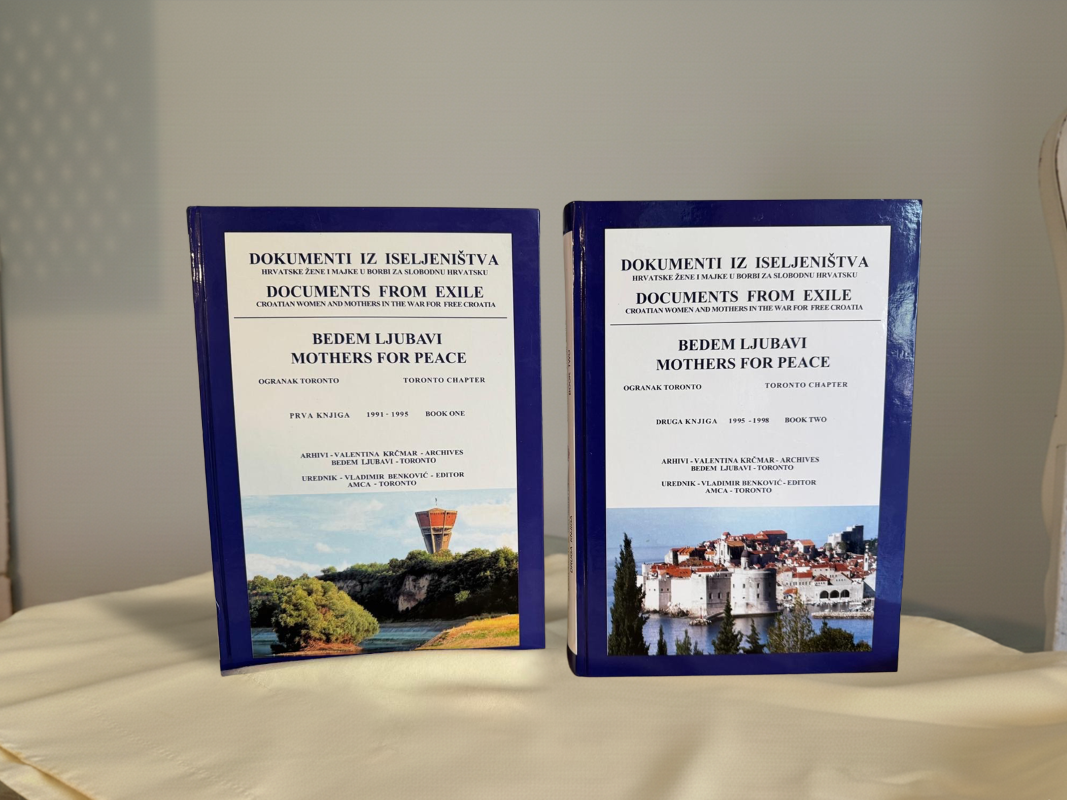

Author: Valentina Krčmar, Thornhill, Ontario

Addressed to: Letters to the Editor, The Toronto Star

View the Original Letter: krcmar book 3_Part3_Part44.pdf

About This Letter

In this letter dated August 14, 1995, Valentina Krčmar responds to The Toronto Star article “Croats Kill Fleeing Serbs: U.N.” (August 12, 1995). Writing just days after Operation Storm (Oluja) — Croatia’s decisive military campaign that liberated occupied territories — Krčmar confronts what she views as the world’s selective outrage and collective amnesia.

Her tone is unflinching, impassioned, and steeped in moral contrast. She begins by reminding readers of the atrocities that preceded this moment — the mass displacement, torture, and murder of Croatians and Bosnians by Serbian forces earlier in the war.

“It seems to me that the world has conveniently forgotten how the hundreds of thousands of refugees first in Croatia, then in Bosnia were treated by the Serbs from the beginning of the war (which, by the way, they started).”

She paints a harrowing picture of those early refugee columns:

“Thousands of scared people, in slippers and nightgowns, with only a plastic bag with some documents, running for their lives; crying children, hungry and thirsty; wounded were tortured and killed — all scared to death.”

Krčmar recounts the systematic cruelty inflicted upon civilians — young women and children raped, men tortured, and those who survived forced to sign “sale” documents under Red Cross supervision, relinquishing their homes and land to Serbian occupiers.

“If they were ‘lucky’ to be offered to let go, they had to pay about 100 DM for the ‘safe passage,’ along with a signed document… that they ‘sold’ all their possessions to the Serbs, and that they would never return back to Bosnia.”

She contrasts these horrors with the treatment of Serbian refugees fleeing Croatia after Operation Storm — an exodus that international media widely reported. Krčmar observes that the world’s humanitarian attention seemed suddenly awakened, but only now that Serbs were suffering.

“Today the Serbian refugees from Croatia are offered water and food, watched very closely by every human rights organization for any transgression (where were they when Croats and Bosnians were dying?).”

Her words cut with irony as she notes that the fleeing Serbs appeared better off than the victims they once displaced.

“Instead of running, they are even travelling in all makes of very modern cars; they did not have to sell any of their possessions and could return any time they wanted — provided they did not commit any crime against the Croatian population.”

Krčmar ends with a tone of grim justice — sorrow for the innocent, but none for those complicit in the cycle of violence:

“Do we feel sorry for them? Yes, but only for the babies and children, because the adults who have committed crimes against their neighbours should have known better. What goes around, comes around.”

This letter captures Krčmar’s moral clarity amid a war clouded by propaganda and double standards. It is both a defense of truth and a demand for memory — a refusal to let the world forget who started the fire before condemning the smoke.