Date: August 14, 1995

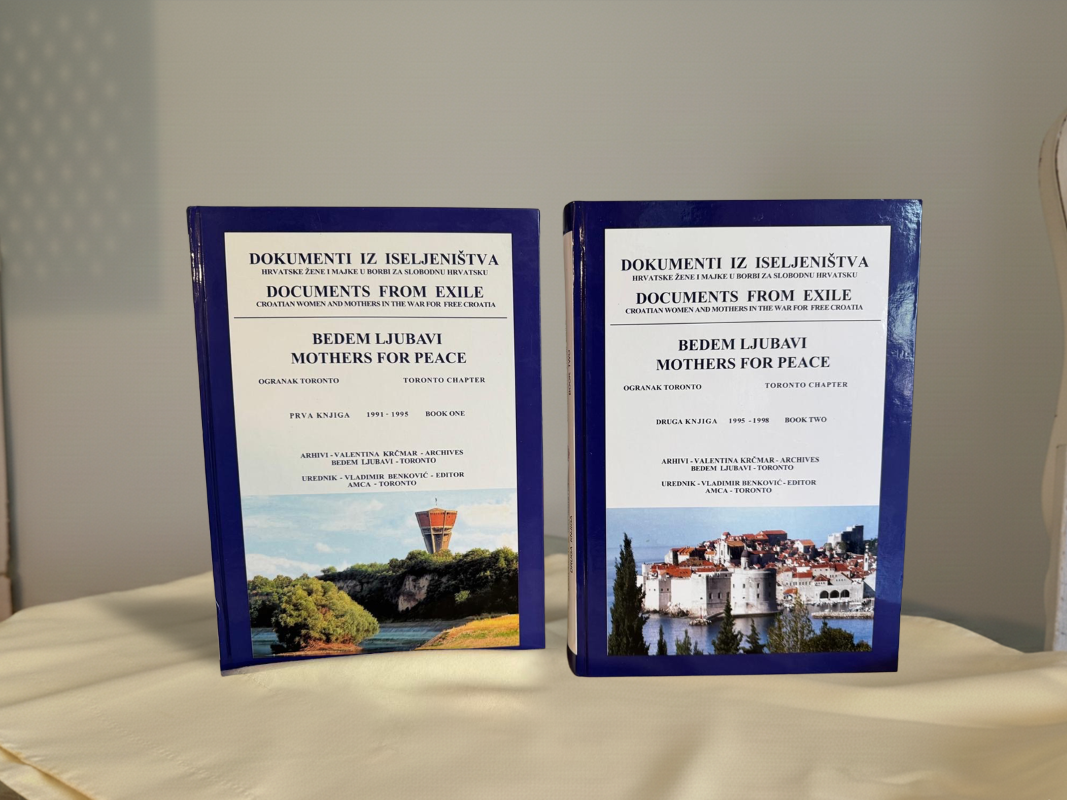

Author: Valentina Krčmar, Thornhill, Ontario

Addressed to: Letters to the Editor, The European (London, England)

View the Original Letter: krcmar book 3_Part4_Part150.pdf

About This Letter

Written on August 14, 1995, Valentina Krčmar’s letter to The European serves as a moral counterpoint to the publication’s piece “Krajina Horde Launched on Sea of Despair” (August 10–16, 1995). Her tone is sharp and unapologetic, challenging the Western media’s sympathetic portrayal of Serbian refugees following Operation Storm (Oluja) — and reminding readers of the far greater, often ignored, suffering inflicted by Serbian forces in Croatia and Bosnia.

Krčmar opens with a direct rebuke of selective compassion:

“It seems to me that the world has forgotten how the hundreds of thousands of refugees first in Croatia, then in Bosnia, were treated by the Serbs from the beginning of the war — scared people in slippers, in nightgowns, with just a little plastic bag with the documents, running for their lives; crying children, terrified old people, many killed.”

She paints vivid images of the first waves of Croatian and Bosnian refugees — civilians stripped of dignity, possessions, and hope — before contrasting their ordeal with that of the Serbs now fleeing Croatia.

“Then Bosnia came when Bosnian refugees were taken off the buses: raped, killed, tortured, threatened, and many of these unfortunate people that fell into the Serbian hands had to pay about 100 DM for ‘safe passage.’ None of these Bosnian refugees had cars, or trucks, or any possessions… because they had to sign a piece of paper which said that they ‘sold’ all their worldly goods to the Serbs and that they would never return to Bosnia — all witnessed by the officials of the Red Cross.”

Her moral indictment deepens as she exposes the hypocrisy of international observers, who, she argues, were absent when Croatians and Bosnians were dying but suddenly appeared when Serbs became displaced.

“Today the Serbian refugees did not have to pay anything to anyone. They even received guarantees from the Croatian government for their safety, they were fed and closely watched by every human rights organization — where were they when Vukovar was falling, or Srebrenica, or Žepa?”

In her letter, Krčmar dismantles the narrative of Serbian victimhood by recalling massacres, mass graves, and the systematic terror Serbs had inflicted. Her tone is not vengeful, but unflinching in its insistence on moral accountability.

“They did not have to ‘sell’ any of their possessions: houses, lands, cars, or valuables to anyone — they just left because they were afraid of what they had done to their neighbors. After all, it is normal that you have to account for all your deeds, good or bad.”

She closes with a line that crystallizes her entire position — one that grieves for the innocent, yet refuses to equate guilt with victimhood:

“Should we feel sorry for them? Only for the children and babies — they are innocent, which can hardly be said for the rest of the Krajina horde.”

This letter exemplifies Krčmar’s defining traits as a writer and moral witness: precision, conviction, and the courage to challenge the West’s moral double standards. By reframing the narrative, she compels readers to confront the uncomfortable question of who the true victims were — and what justice demands when empathy becomes selective.